- Germany -

Modern History

Critical Review: Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

(Peter Eisenman, 2005)

"An invitation […] to search for the memorial in their own heads.

For only there is the memorial to be found."

Horst Hoheisel

The countermonument seeks to address Nazi Germany as perpetrator and present day Germany as rememberer. Faced with the task of remembering immense suffering that can only be conceptualised as a void in German identity, a set of paradoxical and often unresolvable responsibilities arise. The need to: formalize the formless; represent without speaking; remember without resolving; and crucially, address a wound without healing. For Dominick LaCapra, these responsibilities should address how to keep the memory of suffering alive ‘quite openly and not just in our own heads.’ Counter-monumentality, as a critical and commemorative practice, is a deliberate act of ‘working through’ such ethical considerations. It is not an objective to merely argue what Peter Eisenman’s memorial represents or does not represent. Rather, this reading is an attempt to question what is at stake in representation. In other words, to consider the way in which changes in the social and political landscape impinge upon the representation and remembrance of trauma and, concomitantly, unearth new challenges at the individual, generational, and national level. This is, after all, a significant part of the memorial process.

The countermonument attempts to formalize Germany’s obligation to remember and it explores the extent to which current frameworks of understanding and forms of commemorative practice are linked, however unwittingly, to Nazi Germany. For instance, public rituals like Bitburg serve the negative purpose of stultifying the past and expunging its presence today. Additionally, traditional monuments purportedly remember but actually impose a naturalization process that neutralizes meaning and inspires a fixed, narrow act of ‘remembrance’ that potentially occludes memory altogether. As a result, the countermonument is a radical break from established forms, narratives, and rituals and instead demands that passive commemoration is made active and any attempt to resolve is violently destroyed.

The role of Germany as rememberer is deeply attached to the question of what constitutes German identity after reunification in 1989. Additionally, it addresses the relationship the postgenerations have with the Holocaust (what Marianne Hirsch has termed ‘postmemory’). Postmemory, in its simplest form, describes the indirect experience of the postgenerations to past (often traumatic) events that continue to have lived effects in the present. It is an inheritance of memory through stories, photographs and behaviours that are contained within the familial, national, or cultural realm. Postmemory often exceeds the bounds of comprehension, because ‘it is not’, as Marianne Hirsch remarks, ‘actually mediated by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.’ The memory of the postgenerations is not a result of a direct or literal experience nor is it a purely figurative or abstract memory.

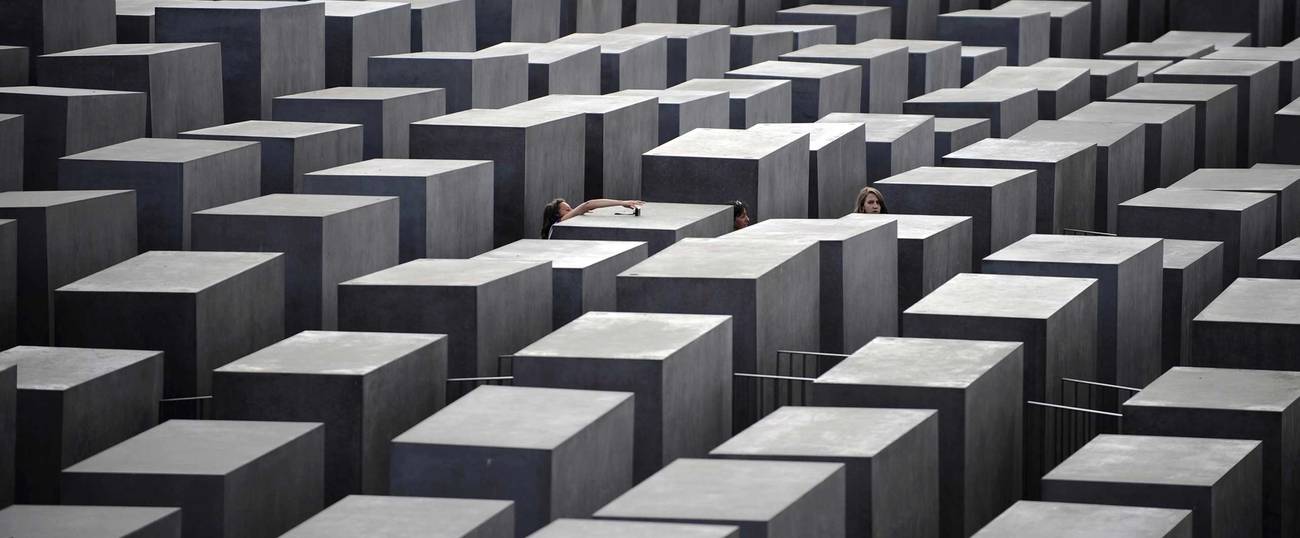

Postgenerations in Germany are at risk of having their own stories overwhelmed by the story of the generation that preceded their birth. Consequently, at stake here is not simply the personal, familial, and cultural transmission of memory, but most importantly, the issue of forging a national identity that radically opposes its predecessor. The formal execution of the countermonument attempts to speak to this peculiar form of memory that confounds ‘normative’ conceptual frameworks. Firstly, it is aesthetically incongruous to its surroundings. As shown it is interspersed within the cityscape which contributes to what James E. Young calls ‘it’s Unheimlichkeit, or uncanniness’ . The ethics of the aesthetic form remain debatable. It could be argued that its incongruity renders it unknowable and alien. In other words, the memory can only be digested when it is considered parallel to, and thus incompatible with, German identity. However, I wish to dismiss this interpretation by addressing the intent of a memorial, specifically in Berlin.

In a literal and material sense, Eisenman’s memorial is compenetrated with the fabric of Berlin and thus imposes itself onto the consciousness of those who pass it. The significance of this can be elucidated by the date 9th November, which is contested in the German political imaginary. Once bearing the painful marks of Kristallnacht in 1938, the reunification of Germany in 1989 threatened to displace the destruction of Jewish identity with the triumph of a restored German identity. The memorial refuses Kristallnacht – and the Holocaust as a whole - a dwindled presence in the political unconscious of Germany because it is part of the restored capital. Therefore, the memorial is an acknowledgement that the trauma inflicted by Nazi Germany will always be central (literally and conceptually) to any renewed identity. ‘Even as’, Young aptly remarks, ‘it threatens such identity with its own implosion.’ Many regard the addressal of German trauma as exonerating Nazi Germany and even obfuscating victimhood. However, as shown, the memorial is incredibly self-conscious and thus critical of German identity today.

From afar, the memorial is indistinguishable and the concrete pillars are, seemingly, homogenous, therefore, it is absolutely necessary to experience this memorial literally. To experience the physicality of the monument is to be become vulnerable to its demands. As Young notes, ‘it demands that visitors enter the memorial space, and try not to know it vicariously through their snapshots.’ It denies indifference or resignation because they have to physically submit to its space and then, they are forced to negotiate it. Once immersed within the space, the pillars become jarringly individuated, yet equally part of a collective. Jewish trauma is no longer homogenised but is given a multiplicity.

The significance of being immersed within the form of the countermonument itself suggests that postgenerations are an active part in the memorial process. The Holocaust may have happened in the past, but it continues to shape lives today. Historical text thus remains absent from the pillars. The written sign is permanent and unchanging and although, interpretations of it may change over time, it remains locked into a fixed past. Therefore, the countermonument does not allow a passive retrospective encounter – like pedagogical sites or traditional monuments. It rather combines the past and its mediation in the present. Especially when the present is unsettled by different social and political disturbances. Arguably, the contemplative memorial inherently contains an alternative pedagogical function that departs from imposing knowledge and instead, invites visitors to reflect on and renegotiate established knowledge.

If the traditional monument represents the past as a fixed moment in time, the countermonument, alternatively, is an attempt to represent time as neither linear nor circular. Indeed, the memorial has no beginning or end or no entrance or exit. It resists the familiarity of the chronological historical process that we are locked into. Young notes the memorial ‘formalizes a […] memory that is neither frozen in time, nor static in space.’ Time is represented as a series of non-chronological disruptions, implosions, and rearrangements. For example, the reunification of Germany was, and still is, a disruption to German identity that threatened to implode it entirely.

The power of this monument, then, resides within the visitor themselves because only then is the memorial process activated. With their bodies in literal motion, their minds are forced to experience the monument. The human subject becomes a necessary vehicle to engender memory. The unstable space enclosed within the formal execution of the concrete pillars can be regarded as synonymous with memory itself. In this sense, pillars offer a space for the performance of memory. There is also a strong sense of renewal which is, importantly, not to be conflated with the possibility of redemption. It would be almost impossible to keep a mental track of the route taken, therefore, memory becomes active and in constant motion. The memorial is conscious of an inability to be complete – conceptually, thematically, or formally – because memory never reaches completion. This, as Young notes, fulfils Eisenman’s goal to ‘foster a sense of incompleteness’.

The countermonument raises questions as it attempts to address (not answer) others. For the artists practicing counter-monumentality, the act of remembering will never resolve or finalise the debate concerned with commemorating the victims of Nazi Germany. To readdress Hoheisel’s point, the memorial offers a contemplative practice that eventually connects to LaCapra’s demand for an ‘open’ process. Perhaps it is the sustained and ‘open’ debate itself that attends the encounter with an artistic work that can be considered a ‘mourning site’. Nevertheless, the countermonument and its attendant questions attempt to disturb any form of fixed memory that is merely preserved in the present and it attempts to create an active and open one.